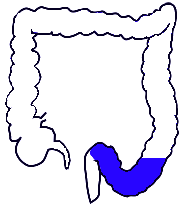

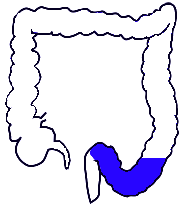

In November 2017, a routine screening colonoscopy revealed

colon cancer—an unhappy surprise in anybody's book—and

I had my sigmoid colon removed in December of the same year

by a very talented colorectal surgeon. Thanks, Dr. Rad!

In November 2017, a routine screening colonoscopy revealed

colon cancer—an unhappy surprise in anybody's book—and

I had my sigmoid colon removed in December of the same year

by a very talented colorectal surgeon. Thanks, Dr. Rad!

Pathology showed that the cancer had spread into a few of the

local lymph nodes: I had stage 3a colon cancer, and chemotherapy was

indicated for me in early January. Happy New Year!

This is the story of my journey from a patient's point of view

with things I wish I'd have known at the time. At all times I had

good medical care, but there were all kinds of things that

would have improved my day-to-day life; I'm hoping to share this

with you.

I cannot emphasize enough: this is not medical advice.

I am not qualified to do anything other than tell my own story,

and at Every. Single. Point. you must defer to the judgment

of your medical team. My advice is typically practical, not clinical.

This is also based on my own personal circumstances, which may not

match yours; I'm a 55 year old male, in good health, with no prior

family history of colon cancer, and receiving

the FOLFOX6 chemotherapy regime.

If your regime is different, your

health is different, your oncologist is different, your infusion center

is different, or if you are not me: your mileage may vary, though some parts may still apply.

In addition, each infusion center (and oncologist) has their own

protocols and procedures, so even if you're on the same drug

regimen as me, it might not play out the same way.

What I also have going for me was an exceptionally positive

attitude, superb insurance, a very deep bench of friends, and

of course a wonderfully supportive wife. I'm self employed, which

gave me great flexibility with errands and naps.

As I write this, I'm on chemo Round 11 (of 12), and I'm not sure I could be any more lucky.

Update: July 2018; I'm now through all my 12 rounds of chemo. Whew!

Update: Sept 2019: Chemo long over, multiple blood tests and CAT scans show all is well. Yay!

Update: Jan 2020: All is still well, and I'm now making updates at the bottom chronologically

rather than update this in place. If you've visited this page before, skip to the bottom.

Disclaimer: Throughout this note I'll provide links to many references

to Wikipedia, and in some cases

to specific recommended products at Amazon.com or other vendors, but I'm not

selling anything and don't get referral/commission from anybody.

Preparing for your journey

Everybody has their own habits and coping mechanisms, and in my

case, as a voracious consumer of science, I empowered myself by

diving deep into the medicine and chemistry of cancer, pretty much

geeking out on details.

Though many of the details really did help me understand what's

going on in my body, making sense of a side effect, many of the

technical details were little more than bar trivia tricks, as

there's nothing you can usefully do knowing that

(say) 5-Flourouracil is a

thymidylate synthase inhibitor.

But even those who don't have the interest that way

can still help themselves: the internet is

a wonderful resource for those going through this, and Google

will be your friend.

Cancer support websites abound, where you can find out that

others are going through the same thing as you: this goes a long

way to not feeling alone.

However your personal inclinations, I can offer a few pieces

of general advice.

- Journal / Keep good notes

- I keep a file on my computer, and I make notes virtually

every day, and this has been incredibly useful.

- Initially I made notes of every phone call I made to

a doctor or insurance carrier while setting up my surgery

and planning for the oncologist: This is really helpful

in case a provider is dropping the ball.

-

That kind of phone-call detail may not come up so much once

you settle into a groove with chemo, but it's then that you

need very good notes on how you're feeling, what you took,

how side effects are going, and all that.

-

If you're going through 12 rounds, you really want to identify

patterns, especially the cumulative side effects. Being able to

tell your doctor that the yuck started to wear off on Day 5 but

the neuropathy hung on until the middle of the "off" week means

they will give you better care.

-

Going to your doctor with a good record of your symptoms is important.

- Bring somebody with you to the first oncologist appointment

- There's so much information to learn, you simply cannot keep

it all in your head even if you take good notes and the doctor explains

well and gives handouts. It's just too much.

- Having a spouse or a friend means they will remember things you

don't, and will ask questions you didn't think about. This is so,

so useful.

- Educate yourself from reliable sources

- The internet is a mixed bag of information: some great

resources, and some not so great, and it can take some digging

to sort it out.

- Personally, I have a strong (but informal) background in

science and have a very good BS detector, so I'm able to easily

separate the good data from the nonsense.

-

And there's a lot of nonsense from all kinds of crackpots,

including those proposing that amazing watermelon cure from

Mexico where you can "detoxify" your way to being cancer free.

-

One I'll call out by name to avoid is Food Babe:

she has a great talent for hyping an entirely science-free position into bad

advice. My blog post

on one of her screeds shows how to think critically, and hopefully

will fine-tune your own BS detectors.

-

Dr. Oz is also to be avoided for any kind of medical advice unless

you're looking for snake oil.

-

You'll also receive well-meaning advice from friends that

it's all a conspiracy by Big Pharma and you should never let

them put that poison in you, instead opting for holistic remedies.

This opinion is often delivered passionately and entirely in good faith.

-

You should of course consider all legitimate treatment

courses, but I'm firmly in the camp of science and modern

medicine, so I thank the giver of this advice for caring about

me so much, and letting them know that I am very comfortable

with my decision given that I really do understand this stuff.

You should of course consider all legitimate treatment

courses, but I'm firmly in the camp of science and modern

medicine, so I thank the giver of this advice for caring about

me so much, and letting them know that I am very comfortable

with my decision given that I really do understand this stuff.

-

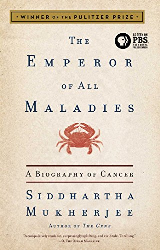

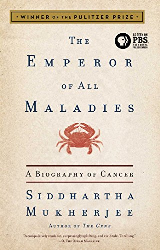

Super reliable source:

I'd be remiss if I did not recommend an outstanding book:

The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer.

This is not a self-help book, not how to avoid cancer by eating right, or anything like that. This is a deep background on cancer, and it's

absolutely fascinating. The author is an oncologist and a damn fine writer: he won the Pulitzer Prize for this book.

-

It's really for the general public, not just cancer patients; I had read it 5 years ago, then re-read it when this

all hit the fan for me, and understanding how cancer works (and how cancer medicine works) can go a long way to

removing a bit of the mystery of this disease. Mysteries are scary: this book helps. Your close circle should all

read this book.

-

And as I write this, I discovered that Ken Burns has created a documentary based on this book: this I gotta see!

- Accept help from friends

- To the extent that you really can use some assistance:

a ride to a medical appointment, somebody to cook for you or make a run to

the grocery store, to sit with you in chemo for company.

Accept their help.

- People commonly wish not to be a burden,

but this is not the time for that. You're dealing with

cancer, you have people who want to help you, and it's a gift

to them to accept their help.

-

Really, it's ok for this to be all about you for a while. Own it!

- Consider making yours a public journey

- Everybody gets to decide if or how to share a private medical

condition, but for me, it was helpful to share this with my wide

circle of friends on Facebook.

-

Unless this is truly a confidential concern shared only with very

close family, your friends are going to wonder how you're doing,

and regular posts make it really easy to

keep them all in the loop. You'll still get asked about it, but

it saves a huge amount of time trying to remember what

you told to whom.

-

This is extra helpful if you actually could use assistance: you

can post your request for help, and you'll likely receive numerous

offers.

-

So many friends have told me how much they enjoy following

my progress, reading the geeky stuff, and how much they want

me to keep posting it.

-

In addition, colon cancer is highly preventable, and we can use our

experience to encourage others to get their colonoscopy. I've had

many friends report they finally got off their (ahem) butt

and got it done. Maybe we can save a life?

-

But this is a very, very personal decision, and the only one to

whom you owe complete details is your doctor (though a spouse

is a close second).

- Expect to feel overwhelmed sometimes

- Most people in this position had it drop upon their heads

suddenly and unexpectedly, and it's an enormous amount

of stuff to just absorb. The combination of the unfamiliar

medical information, the unpleasantness of the regimen, and the

wonder what your future holds—all of this is normal.

- Added to that are those with a limited local support system

or with unusually bad reactions to treatment (or with grim

prognoses), it's easy to see how this could give anybody

pause.

- Share your journey with trusted friends, ask lots of

questions of your doctor and nurses, and do what you can to

clear up mysteries: these all take a weight off. And a good

cry now and then doesn't hurt either.

-

Almost everything about this Tech Tip is here to help make it

an easier journey for you; feedback is welcome.

The FOLFOX6 Chemotherapy Regimen

Variants of the FOLFOX

regime is pretty much the standard of care

for colon cancer at most stages, and because my surgeon believes

he got all the tumor, my chemotherapy is

adjuvant therapy,

which is just insurance in case bits are brewing elsewhere too small to be detected.

The FOLFOX protocol is 12 rounds of two weeks each,

where you'll visit an infusion center on Day 1, spend a few

hours getting some of the drugs, then go home with a pump

attached to your port, then return on Day 3 to be disconnected.

The rest of the time you recover. Rinse and repeat.

The three main meds of this regimen are:

- FOLinic acid

(aka Leucovorin); it potentiates the flourouracil but is not a chemotherapy agent itself.

- Flourouracil,

aka the well-named 5-FU (say it aloud!)

it's a chemotherapy agent that gums up DNA replication.

- OXaliplatin;

another chemo agent that gums

up DNA, but this has the side effects you worry a lot about.

Much more on this later.

I saw my oncologist once a week for the first couple of rounds,

but he made it every other round once I settled into a good rhythm.

My doctor also put in an order for standing blood tests

which I had to handle on my own with a local lab. These are

in addition to the infusion-day blood tests they run automatically.

Variations abound: I am on FOLFOX6, but there's also FOLFOX4 and FOLFIRI,

and there will surely be others available. The ones I named are all on a similar two-week cycle, but I'm only really speaking of

FOLFOX6 in this tip.

Your Port

Because FOLFOX therapy requires you to take home a pump for a couple of days,

there's no way it could ever work with an IV line in the crook of your arm

or in your wrist. It would be a mess.

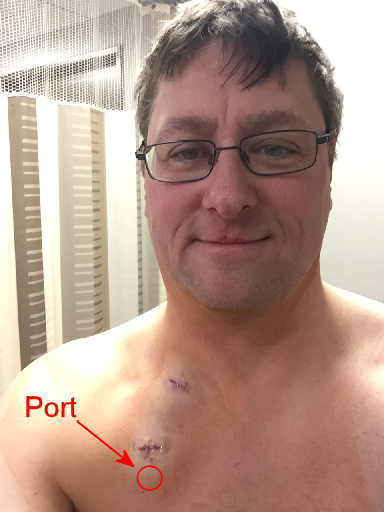

So I believe the standard of care is to have a General Surgeon implant

a "Smart Port" (aka Port-A-Cath, a few other names too) under your skin

in your upper chest, which provides easy access to the bloodstream.

Mine took 10 minutes to implant under local anesthesia, it's common

for patients to drive themselves to and from the procedure: easy business.

You can't really see the port itself in this picture, I've marked the location

with a red circle, and the two incisions were used by the surgeon

to make it so:

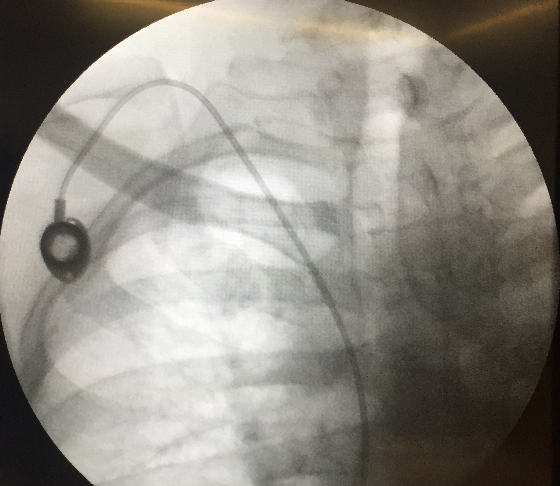

The flouroscope shows it inside:

I really like my port; no getting poked in the arm every time.

For the first coupla days after implantation I had to cover it

while showering, but it was easy to manage.

I call mine "My USB port", and note that it's titanium for enhanced performance :-)

There are two action items I'd like to recommend regarding

infusion day with your port:

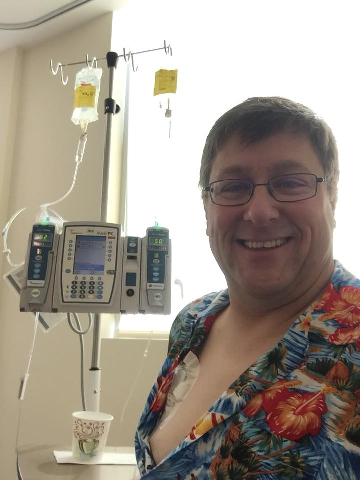

- Easy access for the nurses

-

The nurses have to get access to the port a few times, and

it really helps if you have a shirt that can unbutton all the way.

They can work around a t-shirt, but it's more awkward for them (and you).

-

I've made it a point of wearing a Hawaiian shirt every time

just to liven up the place: the nurses (and patients) seem to enjoy it,

and it's all part of a positive attitude.

-

Here we see the infusion pump (not the take-home one!) hooked up to

my port, along with my festive attire:

-

- Numbing your port

-

The port is just under the skin, and it's pierced with a special

non-coring needle, and this is more or less like most other IV

access pokes.

-

Ask your oncologist if

EMLA cream

is right for you: this is a lidocaine type numbing cream you put on the skin

over your port around an hour before your

infusion to numb the area. It's super cheap and totally safe and many oncology

practices prescribe this automatically.

-

Mine didn't, and I was thankful a nurse friend suggested it.

-

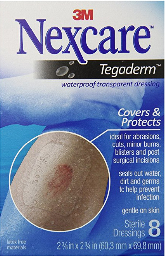

You should cover the cream to keep it off your clothes, but

a regular Band Aid has a cloth-type patch that will soak it up

instead of going into your skin, so I use the same bandages that hospitals use:

-

-

Tegaderm bandages;

about $6 for a set of 8 (get 2 boxes to cover 12 rounds).

-

You'll just put a small dab of the cream in the middle of the

clear sticky area and put it on your port. The nurses see

this all the time.

-

Update: I understand that some infusion centers

use a numbing spray on the port prior to puncture, which

achieves the same thing.

Update: One patient who had his port installed the same

place as mine has reported pain/discomfort when turning his head,

apparently because it's tugging on the tube under the skin. You

can't really see the tube under my skin, but you can under his.

I don't know if there are different techniques used by different

surgeons, if his was done poorly, or if I just got lucky.

Update Oct 2018: My port was on the right side so didn't interfere with

the seatbelt for driving—yes, I drove while connected to the pump—but

a helpful reader who had hers on the left side found that a kind of padding

around the seat belt helped.

Yes, of course there is such a thing: Chest Buddy Seatbelt Cushion (link to Amazon)

The Infusion Cycle

I have experience with two infusion centers in Orange County, California,

but there are likely many variations; you'll get the lay of

the land with yours at your first visit.

- Day 1 - infusion

-

I show up at 8AM at the local infusion center,

and on this day you're pretty much dealing with nursing

staff, not doctors. These are specially-trained oncology

nurses, plus there are often nursing assistants and possibly

even volunteers.

-

You'll step on a scale as you enter because the chemo meds

are based on height and weight, then off to a comfy chair

where routine vital signs are taken.

-

A nurse will access your port with a special needle, and they do this

one time only during your visit.

It hurts just for a second, it's no big deal (especially if you have

used the EMLA cream). The port is great.

-

The nurse will draw blood samples for testing to make sure you're healthy enough

for chemo: if your bloodwork is out of whack, they'll call

the doctor to see what they want, and in some cases they

may defer your infusion entirely until things normalize. I was deferred

twice for low plateletes, and others have been deferred from low white cell counts.

-

Then come the meds:

-

- IV Saline for hydration while waiting for the labs

and the pharmacy.

- If labs are good, pre-meds start: Zofran

(ondansetron) for nausea, plus a steroid to help the Zofran. This is maybe 20 minutes.

-

Then 2-hour infusion of Oxaliplatin and Leucovorin.

-

Flush the line with regular saline to make sure all the "good stuff" makes it inside.

These meds are crazy expensive and they're not going to leave any in the tubing.

-

They hook me up to the take-home pump with Flourouracil,

put it in a fanny pack, make an appointment for disconnection on Day 3,

then I hit the road.

-

The whole time I'm sitting in a comfy chair with my laptop,

I don't feel anything from the meds, they bring me water and

snacks and check on me: it's really quite pleasant.

-

My typical infusion Day 1 is around 4.5 hours, but it was

higher before we all got into a rhythm.

Allowing for 6 or 7 hours for your first time might not be

a bad idea: there's lots of 'splaining going on.

-

Some patients have visitors to keep company, I didn't need

that or really even want that: it's nice quiet time for me to

get some work done.

-

Note that not all patients are in there for the same thing, not

even all of them are chemotherapy patients. But you'll start to

recognize a few of the patients over time, and of course you'll

get to know the nurses really well.

- Home days 1/2/3

-

I'm toting a pump around for 46 hours, and because I work at home

it really does simplify my life. It's no problem to go out,

I just have a tube running from the fanny pack to my shirt,

and nobody's ever asked me what it is.

-

I did put orange racing stripes on mine to make it go faster :-)

and it a bit more festive, and I've never been self-conscious

about it while I was out and about.

-

Showering is inconvenient but doable: more on that later.

-

Sleeping wasn't any problem for me mechanically, in part

because I also wear a CPAP mask for apnea, so this didn't make

it any worse at all.

-

But because the steroid causes insomnia, I always take

a sleep aid on days 1 and 2, at least.

- Day 3 - Disconnect (aka Disco Day!)

-

I return to the infusion center 46 hours after my pump started,

and it's a brief visit: the nurse flushes the line, disconnects

the port and covers it with a bandage.

-

Here is where there can be variation: in my case, I get a shot

of Neulasta,

a "colony stimulating factor" that boosts white-cell production in the

blood to make up for the collateral damage from the chemo.

-

Neulasta is an amazing molecule, but it's crazy expensive, something like

$5000 per shot with insurance negotiated rates (maybe even more than $15000 "retail" cost), and not all insurance covers it. There are other therapies

and some patients just choose to skip it in any case without consequence.

-

I have skipped Neulasta once as an experiment, and at the start

of the next round found that blood work was a little low

but still ok for infusion. Always follow your doctor's

guidance on this.

-

Then it's time to go home after making the next infusion appointment,

a free man without pump in tow.

-

I had a personal reward ritual driving home from disco day to stop at

Arby's and get myself a huge roast beef sandwich. I almost never have fast

food, but with all the crap going on, this was a special treat.

Now the active part of the cycle is over, so it's biding your time

until the next round. Everybody responds differently, but for me

I found the neuropathy symptoms starting on the first day, with nausea

and yuck kicking in late day 3 and all day 4.

Once the "off" week arrives, there's essentially no more yuck for me

and only very minor neuropathy side effects, but I still write this

all down every day.

Let's drill down to some side effects.

Side Effects

I believe that everybody has some side effects, there's

just no escaping it, but there's a very wide variation in body

response and seriousness of side effects.

My understanding of chemotherapy is that FOLFOX is not nearly as

unpleasant as other kinds of chemo (breast cancer, for instance, is

a much worse experience than this), so in some respect we have it

easier than many others.

My doctor has told me, and I have confirmed elsewhere, that

severity of side effects does not correlate

with effectiveness of chemo. I always took this to be a relief

that you did not somehow have to hope for a bad time in

order for the chemo to be effective.

- Hair loss

- It is uncommon to lose your hair under FOLFOX; good news!

There may be some thinning, but I still have a full head of hair after

9 rounds. Edit: still full hair 18 months post-chemo.

-

I couldn't care less about my own hair loss, but understand this is

a very emotional issue for many, and we can be thankful we are

generally spared this.

-

In regimens for other kinds of cancer, hair loss can start on round one.

- Nausea and Yuck

-

Everybody expects nausea during chemotherapy (and radiation if your

regime includes it; mine doesn't), but this doesn't go far enough to

describe it.

-

The Yuck is an overall feeling of malaise, a crappy lousy feeling

that makes you feel bad all over even without the nausea, and for me

it starts mildly on Day 1.

-

I've been at a loss to describe it, and the closest I can come is that it's a bunch of

prodromal symptoms that

never materialize: you feel a headache coming on but don't get the

headache, you feel the flu coming on but don't get the flu.

-

It's just a big bundle of yuck that you really, really want to go away. A lot.

- Peripheral Neuropathy / Cold Sensitivity

-

This is the one to pay attention to: it's a tingling or pain in your hands

and feet, often provoked by cold, so if you reach into the fridge to grab

a can of soda, you'll feel a nasty zing of pain in your fingers.

-

Caused by the oxaliplatin, the cold sensitivity shows itself while

drinking a cold drink: it feels like liquid cactus in the back

of the throat and is very unpleasant. I've switched to drinking

room-temp water, and even that sets it off sometimes.

-

IMPORTANT: though nausea and yuck goes away completely after

chemotherapy is over, the peripheral neuropathy is cumulative and is likely to persist

after therapy ends, possibly fading away over months. And for some,

the symptoms become permanent. Yikes!

-

This is why it's so important to keep really good notes of how you feel

in every round and report it to your doctor so they can modulate

the dose down, especially if the symptoms continue into the "off" week.

-

The doctors typically speak of "activities of daily life", such as

buttoning a shirt, but for me, the peripheral neuropathy mainly

impacts my typing on a keyboard; that's my whole life (as

I type this now, my hands are cold and tingly, and it definitely slows me down).

-

In my case, these symptoms were troublesome enough that my doctor reduced

the oxaliplatin to 75% by the fifth round, and to 50% ih the tenth round, and it helped a lot.

We're basically playing "chicken" with oxaliplatin by planning for how it will be

six months after chemo.

-

Update for round #10: Up to this point, all the neuropathy symptoms

were acute, in the sense that they emerged right after infusion, and then faded

as the round progrssed. But my Round #10, the chronic neuropathy symptoms

started to come into play: these are milder but hang around longer and are not

so related to cold. It's hard to describe, but it just feels like this is

the kind of thing that will hang around longer.

-

These symptoms are not troublesome for me at all, but their emergence lags

the treatment, and we expect them to continue growing even after chemo stops, after

which the curve tips over the top and heads back down. The big question is how far

down will it go. We'll find out.

-

The good side, though, is that cold sensitivity to liquids completely went away,

so I was able to drink ice water at any time, and I suspect that better hydration

may have helped make round #11 easier for me.

-

Update for Round 12: the neuropathy has increased markedly, and it's for sure

not related to cold sensitivity. It's become painful and unpleasant, though not enough

to keep me from my work. I do expect it to continue to ramp up after the yuck is over,

but we have no way of knowing how it will progress.

-

The main impact has been trying to sleep: toes are very sensitive to even the light

touch of sheets, and it's not easy to get comfortable.

- "First bite syndrome"

-

Related to the peripheral neuropathy above, but a separate item because I added this

in Nov 2020 when I learned about it from two different people on the same day.

-

First Bite Syndrome is pain/spasms in the jaw muscles when taking the first bite

of food during a meal, with the sensation decreasing through the meal but coming back

after a break.

-

It might be on both sides or just one side, but it's related to muscle movement

part of eating and not the tasting part. It's said to be uncomfortable, and though

I'd not heard of it before, looking back I might have had a mild case of it but

it apparently wasn't prominent enough for me to investigate.

-

I'm pretty confident this is due to the always-helpful oxaliplatin, showing up

just after infusion, and fading away over the course of the cycle. I don't think

it's one of the permanent neuropathy side effects, but of course you should

always take good notes on when the symptoms start, how serious they are, and when

they start to face away: this is very important that you record this for your doctor.

- Mouth sores

- This didn't happen to me, but it's common enough that the nurses ask me

every time. They will recommend some kind of saline rinse to have ready in case

the problem arises, but I've not been there myself.

- Weight gain, but not really

-

The steroid they gave me during Day 1 infusion caused water retention,

so I would typically gain 5 or 6 pounds over 2 days (!!), but it always goes

away right after. It's alarming but not something to be concerned about

(but still report it to your doctor).

- Day 1 Insomnia

-

Our friend the steroid will also keep you crazy wide awake on day 1,

it's just one of the side effects, and many can make use of a sleep aid.

In any case, talk to your doctor in advance so you're ready on

the evening of Day 1; some sleep aids are more appropriate than others.

- Constipation / Diarrhea

- Your colon has been through a lot during surgery, so you've probably

already gotten a fair handle on your own digestive system, but the chemo

will definitely stir it up with one symptom or the other.

-

Patients who get diarrhea have to pay special attention to remaining

hydrated, but it never happened to me. I had the "slow" version of

symptoms and constipation was an ongoing struggle for quite a few

rounds.

-

It's hard to describe just how big a quality of life issue severe

constipation can be: chemo hasn't made me throw up due to direct

nausea, but constipation has. It can get really bad, especially

with the speed-up/slow-down that comes with use of the very effective

Milk of Magnesia.

-

Fortunately, my family doctor put me on a regimen that worked super

well for me, so I've been a "regular guy" for weeks now, and it's just

so nice to have this be a non-issue.

-

I'm hesitant to spell out the actual regimen because only your doctor can

evaluate you properly, but it involved Miralax and Colace.

- Lhermitte's Phenomenon

-

This one is apparently uncommon, and though it's somewhat related to the

peripheral neruopathy, it's not the same. For me, it manifests itself as

a curious sensation on the soles of both feet when I nod my head. Really!

-

This phenomenon

is rooted in the spinal cord in your neck, and though my version is really

mild, it can be much more pronounced as it manifests as a shock running down

your spinal cord and down your legs.

-

This was a fun one to figure out: I noticed I had these odd tingles in my feet

but could not figure out what was provoking it, but one evening while watching

TV with my family and my feet propped up on the table, I felt it while I noticed I was nodding my head.

-

Huh?

-

A few intentional nods completely nailed the cause, and it didn't take long before

an internet search showed what it was.

-

My understanding is that it only happens later in the regimen (if at all),

and it's generally benign, but always report it to your doctor if you feel

this head-nodding-provoked sensation. Mine went away shortly after chemo

was done.

-

And to be clear: it was completely painless for me, only interesting,

and absolutely nothing to fear.

- Other side effects

-

There are many other possible side effects, you'll get the whole list

from your doctor and/or nurses, and it's good to keep an eye on this.

-

I am not touching on these other symptoms because they didn't

happen to me, so there's not much I can really offer.

-

But I strongly recommend you make notes of everything you

experience, even if it's not on any list, and report them to

your doctor: your journal will help you get more comprehensive care.

Learning your cycle

Each chemotherapy cycle is two weeks long, with infusion on Day 1,

disconnect on Day 3, and all the rest working your way to the next round.

For me—and everybody is different—the very first days 1 & 2

were no problem at all, and when I saw my oncologist on day 3, I was

thinking: this isn't so bad! For some patients, a mild, low-level

yuck is all they get.

Then the evening of day 3 came and took a nasty turn, and day 4 was

truly miserable. Very unpleasant nausea, overall yuck that lasted all day

spent mostly in bed. I couldn't really sleep, just rested and felt crappy.

The more worrying thing for me: is this just one bad day, or the windup

to a bad week? Thankfully it was the former, with symptoms

winding down on Day 5 (Friday for me), and mostly recovered by the weekend.

The second "off" week was really quite nice, I was pretty much my old

self and was able to participate in a routine life until the next round.

The second round was much like the first in a strictly clinical way,

but because I knew what to expect, that made it much easier. But the

symptoms are cumulative, so round 2 was worse than the first,

and—again—this is where you should be keeping notes for

your doctor.

After one or two rounds, you'll have a sense for what your cycles are

like: How bad are your bad days? When are your bad days? How

is the digestive tract reacting? How are you sleeping?

These are things you get a handle on with experience and with

consultation with your doctors, and with that you'll be able

to plan.

You will definitely find that your whole life revolves

around where you are in your cycle: busy all Day 1, plan for nothing on

Yucky Day 4, and plan on that super fun party on day 12 because you feel

great (or whatever works for you). I have a big red "X" on all Day 4s

in my calendar for the rest of my treatment so I know whether I can

go to that fun party two months from now.

Regarding alcohol; your doctor will probably recommend

avoiding all booze for the first 3-4 days of your cycle: your

body (and liver) are going through a lot, and it's better not

to add more challenges.

My doctor told me I could drink on the "off" week, but I mainly

choose to save that only at the end of that week even though I

feel fine for the rest. I have a weight-loss goal in order to

receive a knee-joint replacement due to arthritis, and the

reduced alcohol has helped.

Nausea and Yuck Control

The doctor will certainly prescribe an anti-nausea medicine,

probably Zofran, but there are others, and if your yuck

produces difficult bowel issues, they'll certainly help on

that front too.

Zofran pills are available in multiple dosages

(4mg and 8mg, at least), plus there's a version

that you can dissolve under your tongue if the

nausea is so bad you can't keep your meds down.

I don't care for the dissolve one because it

leaves a lingering taste in my mouth, and I've

never had problem keeping food or meds down.

A number of friends have suggested ginger in various forms:

gum and teas and ale, mainly, and they do help take the edge off the

nausea. And because of the cold sensitivity, taking a hot

ginger-lemon tea is just a pleasant beverage in its own right.

But there is nothing the doctor can give you that will take

away all the yuck, and it's on this topic that your friends

will come out of the woodwork to ask: have you tried cannabis?

I did my first two rounds strictly by the book, and though the

nausea control helped some, the rest of the yuck was just awful.

So with great reluctance I decided to go down the cannabis road,

and I'm very glad I did.

Cannabis is legal in California for both medicinal and

recreational purposes, and both my primary care physician

and oncologist totally approved this: you do what you need

to do on the bad days.

The two main parts of cannabis are THC, which gets you high,

and CBD, which eases nausea and pain. Both work together to

reduce the yuck on the bad days. There are strains and

varieties, but I've not gotten enough experience to know

about them.

My first foray was into edibles, small chocolate squares with 5mg

each of THC and CBD, but I didn't find that it worked well for me.

It takes quite a while to kick in, and I probably just didn't take

enough.

IMPORTANT: You really have to be careful when taking

edibles for the first time, try a small dose and then wait

two hours before trying more. Not kidding.

It's remarkably common for a novice to take something now, take more

after 30 minutes when they don't feel anything, and again after

60 minutes. But at ~90 minutes it all starts kicking in and you

become a local YouTube star dancing on the table in your underwear.

Seriously, first forays into edibles must be done carefully

until you know what you're doing. Ask the dispensary shop for guidance on this.

I hate cigarette smoke, so I tried the vape pens which don't

cause the cough so badly, and this took a while. There's a huge

variety of product in the vape pens, and it was several of them

before I found the right product and how to properly dose myself.

The first time I used a vape pen, I was sucking on it like it was

a really thick milkshake, a large effort that made me think I was

doing it wrong, but it turns out I was doing it waaaaaaaaaaaaay

right, and I got completely blotto within 60 seconds and just

crashed in bed.

It wasn't at all unpleasant, so I see why people do this on purpose,

but it was clear this was way too much for me, and a smaller dose

worked better when the real yuck came around.

Because I didn't know any better, the original plan was not that

far off from just getting completely stoned on the awful Day 4

so I could sleep it off: I hated the idea, but my doctor said this

was fine, and it helped a lot.

Remember: the CBD is for the nausea and the THC high is for the yuck,

and on the bad days you really need them both. Chemo is not just about

nausea.

But as I studied the cannabis market, I kept learning more about it

and trying new products, and I've really dialed it in with a product

that works super well, it doesn't make me cough, and I can actually

work on my Yucky Day 4!

Taking a single hit when I feel the yuck come on is something I

can only barely feel in my head, so it's not like I'm getting high,

but I just feel better. I'll do this several times a day.

The product I like is from a company called "Dosist" (dosist dot com; I won't

link to cannabis sites from my consulting website). They make

a number of blends that mix up the THC, CBD, and sometimes flavors,

but I settled on the "Relief" blend that has a THC:CBD ratio of 2:1.

The vape pen itself has no buttons, you just take a draw like with a cigarrette,

and it delivers a 2.25mg metered dose in about 3 seconds, vibrating slightly

to let you know it's done. There's a kind of vapor expelled, but there is

no "pot" smell left behind for somebody to notice.

It's easy and reliable to use, and this blend has been perfect for me,

and I am encouraged that it will make my remaining rounds easier.

I've also started with the Dosist "Sleep" blend, which is mostly THC,

and it does a great job of putting me out at night so I get a good night's sleep.

The added THC makes me cough more than the "Relief" blend, but this stuff

has just been easy and reliable.

As with the edibles, I also think it's a good idea to practice this the first time

when you feel good: you need to know how your body reacts to

this new medicine, what dose to take, and how it makes you feel.

Doing this for the first time while in mid-yuck means it's harder

to get that know what caused what.

But unlike edibles, the vape takes effect right away, within a couple

of minutes: you don't need to wait two hours to take a second hit if

the first one didn't do anything. It's best to ask your "budtender"

(the person behind the counter at the dispensary) for advice as a

newbie

Having a trusted friend at hand is a good idea too, just to keep

an eye on you (perhaps with camera at the ready!).

Update for Round 12: the peripheral neuropathy has gotten really

uncomfortable, and I tried rubbing in a CBD-based balm, but

it made no difference after repeated attempts. I don't know if

a THC-based balm would make any difference but ought to try it.

Online research suggests that smoking/vaping of various kinds of

cannabis might help, but it's not bad enough for me to go there; I've

not vaped since day 5 of my 12th round.

"The Stigma"

Side note: I've never done recreational drugs in my life, and

the casual tone above - taking a hit, getting stoned - did not

come easily to me. I was very uncomfortable with the whole

concept, the stigma was strong with me, but I really just got over

it.

It helps me, it's medicine that my doctors approve of, and that's all what I care about.

When I'm on the Bad Day and a hit makes me feel better, it does not cross my mind

that I'm doing something wrong. Holy crap no.

I got comfortable enough to post this on Facebook, which was

a fun conversation to have with my friends; I got 100% support from everybody.

Perhaps you're in a position where you can't be seen

going down this road; I hope you find a way to do it

privately.

As of Oct 2018, I haven't used cannabis since day 4 or 5 of my final

round, and don't expect to again: I was thankful it was available to me,

but it's not something I care to use again.

Random tidbits

Not everything exactly fits in a category, so these are just some notes

in no particular order; I wish I'd known a bunch of these things.

- Insure you have nausea meds before your first infusion.

- Virtually all chemotherapy patients need antinausea

medicine on hand at home—Zofran is very popular—but it

requires a prescription.

-

This is an automatic part of the new-patient intake system for

just about every oncologist, but balls do get dropped,

possibly putting you in an unhappy place if the IV Zofran wears

off on Day 2 and that's your bad day.

-

If you don't have an anti-nausea prescription by the time you're

making your first infusion appointment, ask the nurse and

follow up until you get the Rx. Be persistent about this until you

either have an Rx in hand, or receive a satisfatory explanation of

your alternatives (aka: until you're sure they haven't just dropped the ball).

- Protecting your port in the shower

- The requirement to protect your port from water makes

showering more of a hassle, and unless you can go 3 days

without a shower, you're going to have to find a way to

do it.

- There are many ways to protect your port, but I have found

what works well for me: large clear-plastic water barriers,

and they're easy to order from Amazon.com:

-

-

I put the 7" square right over the port, then put the 9" one fully covering that, then

push all around to make sure it all sticks. You do have to stretch around to make sure

that (say) reaching up to wash your hair won't tear stuff loose, but you'll get used

to this over time.

-

These particular Shower Shields work well.

- Shower just before you head to infusion

- This is all highly subject to your own personal

practices, but I'm a shower-before-bed kind of guy.

-

The requirement to protect your port makes that more difficult,

so I always shower just before I leave for infusion at

7AM. This will last me through the day and night, so I'll go

the hassle of a shower on Day 2.

-

Then, after disconnection on Day 3, I come home and enjoy

a nice hot shower. You don't have to protect your port after

disconnection.

-

As I get better with the hassle, I do sometimes take a shower

every day, but it's nice to not have to.

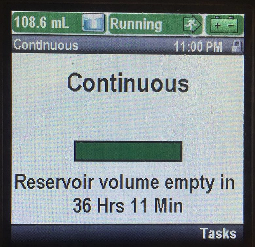

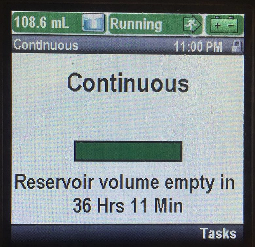

- Know your 46 hours

-

That's the infusion time on the take-home pump,

so it means that once your pump is connected, you'll

show up 2 hours earlier, but 2 days later.

That's the infusion time on the take-home pump,

so it means that once your pump is connected, you'll

show up 2 hours earlier, but 2 days later.

-

Example: pump hooked up at 12:30PM Monday, disconnect 10:30AM Wednesday.

-

Some pumps show the time remaining (see image to the right), but my first pump did not,

and the Day 1 nurse didn't tell me about this or do the math. So I

showed up for my disconnect appointment with an hour remaining,

making me cool my heels until it expired.

-

It wasn't a huge deal to waste an hour, but it was completely avoidable.

That never happened to me again.

- Get dental work done before chemo

-

Your doctor will probably tell you to avoid non-emergency dental

work, including routine cleanings, while you're undergoing chemo.

Dental work causes systemic infections surprisingly often, I suspect

because poking around in gum sockets where there's bacteria festering

is likely to make its way to the bloodstream.

- Because your immune system is compromised during chemo due to

the reduced white blood cell count, it's wise to move up your

routine cleaning before you start chemo.

Post Chemo

I'm writing this in October 2018, roughly 3 months after my last round - I feel great!

One of the first things I noticed was how great it is to regain control of my own schedule.

During chemo, everything revolves around your two-week infusion cycle, so it's hard

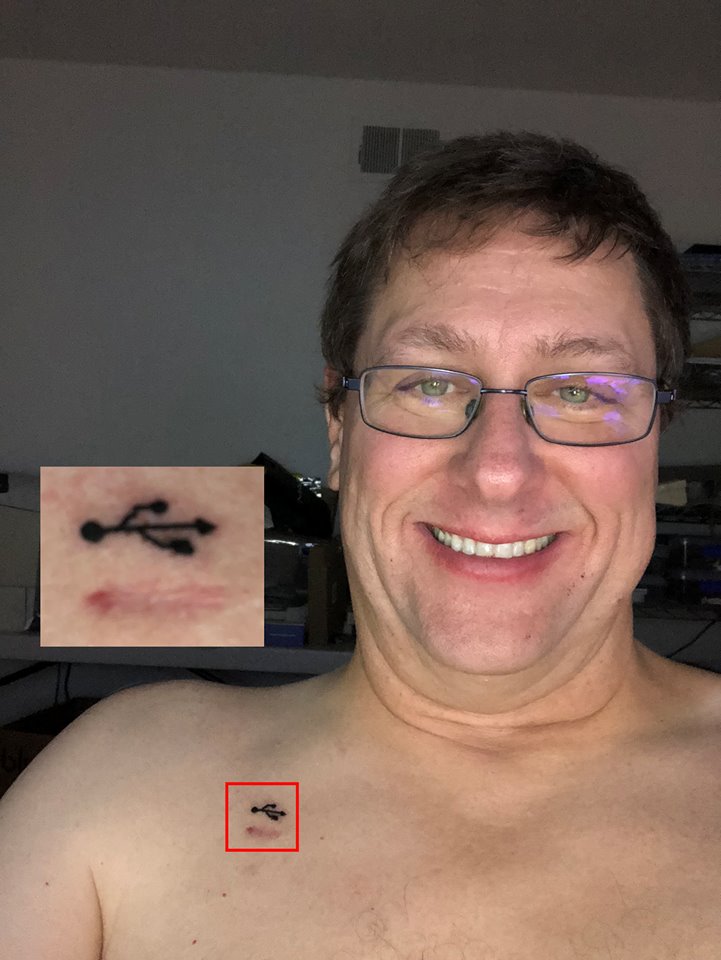

to plan events: will my friend's birthday party six weeks from now be during the "off" week?

Will I get deferred a week for whatever reason, throwing the rest of the schedule off?

I still have medical appointments now and then: I expect blood tests every three months,

plus a CAT scan every year to make sure stuff hasn't come back, but it's much, much

more of an ordinary life now. You just can't imagine how great it is to regain control

over this part of my life.

Around five weeks after my last round, a final blood test confirmed that I was in good shape—including a

nice low CEA value—my doctor ordered removal of my port. They don't do this if there's some chance

I'll need another course of chemo (which sadly does happen for some folks).

Surgery was quick and relatively painless, and I got to take the port home (where I thoroughly cleaned it!).

The port itself is just a hair under 0.5" deep, and the removal scar was tender for a while.

As I had been calling it my "USB Port" the whole time, including on the day of implant, I

followed through by getting a tattoo to "label" the port just above the removal scar:

I've never been the tattoo type, but this just felt right. I've gotten no pushback, and I

enjoy rocking out my geek nature.

That aside, the only real lingering effects are the peripheral neuropathy, the tingling and/or deadness

in my fingers and toes. It's unpleasant but mostly doesn't impact my day-to-day life. My physician

has had me try gabapentin, and then the crazy-expensive pregabalin (Lyrica), which so far aren't making

any difference. This may be one of those things I have to live with until it fades away.

Stay Positive

You'll hear this from everybody, but it's true: a positive attitude

makes a big difference, and it can literally save your life.

I'm fortunate that I'm naturally optimistic, I say the glass is

two-thirds full, so it came easy to me to be upbeat during this

whole process, especially since this is only "insurance" chemo

because they don't think I actually have cancer.

Those with more difficult diagnoses, especially Stage 4, may

well not have the same underlying glowing future, and even

the most optimistic person will find it hard to be chipper

on the bad days.

The best way I found to stay positive is to regain as much control

of the process as I could, mostly revolving around understanding

everything. Knowledge is power (and empowering), and I'm fortunate

that I have a high capacity to absorb it.

Also, mysteries are scary, so if you find yourself

worrying about something you don't understand, ask!

Almost all oncology centers can refer you to a support group; I

didn't feel like I needed one, but others I know have found them very helpful

because you're not so alone when you're not the only one. And getting

practical tips for daily living, especially for the more advanced

cancers, will improve your quality of life. Plus, you get a chance

to help others.

Remember: if you bail on chemotherapy before your prescribed

rounds are over (normally FOLFOX is 12), you've reduced your

prognosis. Do what you can to find a way to stick with the

program.

Update: mid-January 2020

Previously I updated things in line, but will start doing it down here so it's easy to find the changes

(no fun to have to scan pages looking for something new).

First: I'm doing great. All post-chemo scans and blood tests have come back negative, and it's been clear that

other than routine monitoring for a while, this cancer is behind me. I'm very grateful for this.

I've also been grateful for the many notes I've gotten from fellow warriors as they share their own experiences.

It's odd the things that bring people together, right?

Some notes and tidbits:

- My Port

- Though my experience with the port was really good, not everybody's is. One of my pen pals, T., had

so much pain from the port that infusion was put off until it could be removed and reimplanted on the other

side, where it was much better. The doctors never figured out what caused this, but it's the first I'd heard

of it. I'm sorry she had to go through this.

- CEA Blood Tests

- I've been asked about my CEA numbers, and they've been great.

-

The CEA blood test look for a tumor marker for

colon cancer, and I have this test done around every four months (along with an annual CAT scan w/ contrast). Anything

below around 4 µg/L is considered normal, and mine have consistently been in the 1.1 range, which says "no cancer".

-

What it's mainly looking for, I understand, is whether any of cancer cells that should have been fully

removed by surgery (or quashed by chemo) might have wandered about and taken root somewhere else, and a rising

number suggests that.

-

One friend, E., has had her CEA in the range 6-12, and it's had the doctors concerned, but they can't find

where it's coming from and it's completely asymptomatic, so apparently they're in wait-and-see mode.

-

But another dear friend S. in stage 4 had her number in the hundreds, and her story ended very sadly.

- NOTE: CEA is not used as a screening or detection test for colon cancer; it's not reliable enough

(some colon cancers do not throw off this marker), so you can't replace a colonoscopy with a blood test. Dang!

-

Still, with all these caveats, it's the first number I look at in my blood work, but I always review all

my test results with my doctor. So should you.

-

- Peripheral Neuropathy

-

The tingling in my hands is essentially all gone, I have to think really hard to detect it, and even then it's nothing.

-

My feet are a little worse, and this only manifests itself at night with the bedsheets on my feet. It's so minor that

I mostly don't think about it, and as far as I'm concerned, this is a non-issue in my life. This tells me that my

doctor threaded the needle properly on the Oxaliplatin dosing.

-

I have no cold sensitivity of any kind.

- Donuts!

-

I really feel like I have to re-emphasize the benefits of bringing donuts to your oncology center

to share with the staff (mainly nursing staff).

- The first time, of course, you need to pay attention to how the process works and to get

the lay of the land: you'll be there for a few hours and will get a sense for who's who and

how the place works.

-

But on your second visit, consider stopping into a local donut shop and picking up a dozen

that you present to the staff. I always got a box with ½ regular donuts, and ½ premium, and

it's hard to overemphasize how much they appreciate this.

-

Always take care of people who take care of you.

-

Nurses will take care of you whether you're nice to them or not, but it makes the world a better place

when you're nice to nurses (my sister is a nurse).

-

Really: this is a big deal, and the Universe will thank you.

Update: Jan 2022

It's been a long time since my last update, but I'm doing great. CEA test this month showed 0.6 ng/mL,

which is down in the basement, I get another CAT scan in March, and once COVID calms down I'll be

getting a followup colonoscopy.

And the end of this year will mark 5 years with no evidence of disease, which is the usual

point where the onco docs say I'm done. Really glad to be here.

- Pandemic impacts

- It's clear that the coronavirus has changed everything, including protocols for chemo patients.

I understand that most places don't allow visitors during infusion, and though it wouldn't have made

any difference to me, this is a big deal for many who need more support.

- In addition, those undergoing chemo have reduced immune function, so all the responsible things

(masks, social distancing, staying at home) are doubly important. Some patients might choose to

completely self-isolate, which may include those in the same household.

-

It's a scary time; please get vaccinated if you can.

- FOLFOX for bile-duct cancer

-

I had a pen pal note that his father in law with bile-duct cancer was just switched to

FOLFOX, something I'd not heard of before. D: I have him in my thoughts.

- Peripheral neuropathy update

-

The tingling in my fingers and toes had continued to decline steadily since I was done

with chemo—side effect of the oxaliplatin—and though in my hands it's

essentially gone, for unknown reasons my big toes have become noticeably more sensitive

-

This is just in the last few days, and though it's not impacting my life, I can tell

something is going on; I'll be letting my physician know about this on Monday.

-

Note that this is almost certainly not gout,

which mainly impacts the joints: this is not that.

-

This might just be normal variation in ongoing symptoms, but with an extra sensitivity

to any symptoms during a time of pandemic.

-

Nothing about this concerns me.

- Soreness after port installation

- Expect your port to be red and sort after implantation surgery: it probably won't hurt immediately after

due to the local anesthetic, but this is still surgery and anesthetic wears off and it's going to be sore and maybe

even red and angry.

-

This is normal, though complications do happen and you should keep your eyes out for it getting worse,

or if it appears to be getting infected. When in doubt, contact your doctor (helpful reader M. suggests

texting a picture).

- "First Bite Syndrome"

-

I updated the side-effects section to include new-to-me First Bite Syndrome, which is pain in

the jaw while taking the first bite of food. I heard about this from helpful reader H., and

later reported to me the same day by reader M.

-

See above for more info, but this is probably in the same category as cold sensitivity:

unpleasant feelings at the start of each cycle that go away later in that cycle.

- Vitamins and supplements

-

It's important to tell your doctor (or onco nurses) about all the meds you're taking,

including over-the-counter supplements. Most will be fine, but you'd hate to find out

that some seemingly-innocent supplement was interfering with your particular regimen. Surprises

are not uncommon.

- "Butt Paste"

-

As noted above, there's almost no way to go through this without the digestive system

ending up in an uproar; for some (like me) it slows things down but for others it

speeds things up and they spend a lot of time in the bathroom. Neither one is fun.

-

Helpful reader M. has noted that Boudreaux's

"Butt Paste"—a great product name if I ever heard one!—has been a lifesafer. Nominally meant for

diaper rash, it's soothing and does the things you would expect in circumstances like this.

-

I haven't used it myself but have some on order for my next colonoscopy prep.

- Cost of Neulasta - it's crazy expensive

-

Fellow patient M. asked me what the heck this crazy line item was: "Injection Pegfilgrastim 6mg" for about $15,000 (!).

This is Neulasta, it's crazy expensive, but that's just the retail price: her carrier paid less than $4k for it

due to negotiated rates. Still very expensive, of course, but it's an amazing molecule and will get you

which is still very expensive. But it's an amazing molecule that does a really good job at keeping your

white cells up.

-

Low white counts make you more susceptible to infection, and if you go into an infusion

cycle with low counts, you'll be deferred. Nobody wants this process to drag out any longer

than necessary.

- Support Groups

- I noted in the main part of this paper that I didn't really see the need for a

support group for myself, and I'm going to amend that somewhat.

-

As far as emotional support, I always felt completely comfortable with my circumstances,

was never concerned about my outcome, and had a very large circle of family and friends to help

me through. I don't remember ever feeling alone or worried - I'm just a really positive guy.

-

On the other hand, process support can be useful: the mechanims of chemo, navigating insurance,

managing symptoms, I could have benefitted from being in a community with others who had

been there already.

-

Actual medical advice should be sought from medical professionals, but having a place to ask

"Is this normal?" during a chemo round might have been helpful (in fact, this is one of the reasons

I wrote this paper in the first place).

-

So: finding a support group—even an online one—would serve both of these purposes

well, and I'm going to encourage everybody to find one.

-

This is especially the case for a private support group, where you'd be able to speak

freely about your journey that you would not do in public. This includes being able to have

indelicate discussions about the effects of traumatic surgery on your digestive tract.

-

Those going through FOLFOX (or spouses) are welcome to contact me; I might be able to

help you find a resource.

Update: Jul 2023

I'm behind on this update, but all is well.

Since my adventure, all scans - both CAT and bloodwork - have shown no evidence of disease, so

in Dec 2022 my oncologist discharged me from his care: I was no longer a cancer patient.

And after a colonoscopy in March 2023 that included the removal of two unconcerning polpys,

I'm now fully 5 years clean post diagnosis.

I expect to still have CEA blood tests once a year or so, plus colonoscopies at whatever interval

my doctors tell me, but at this point I'm now a civilian again :-)

I'm grateful for the support I've received from my family and friends, but I have to

say that being able to help others via this Tech Tip, plus the many emails I get, have

been good for me also.

Unless something big changes, I'm unlikely to post many updates going forward.

Thanks for following.

If you or a loved one is on this same journey, I welcome your emails

with questions or comments.

Grammar note: My use of singular they

throughout as a gender-neutral singular pronoun is intentional.

First published: 2018/04/18 (my Round 8 Day 2)

Updated: 2023/07/29

![[Steve Friedl Logo]](/images/unixwiz-logo-140x80.gif)

In November 2017, a routine screening colonoscopy revealed

colon cancer—an unhappy surprise in anybody's book—and

I had my sigmoid colon removed in December of the same year

by a very talented colorectal surgeon. Thanks, Dr. Rad!

In November 2017, a routine screening colonoscopy revealed

colon cancer—an unhappy surprise in anybody's book—and

I had my sigmoid colon removed in December of the same year

by a very talented colorectal surgeon. Thanks, Dr. Rad!

You should of course consider all legitimate treatment

courses, but I'm firmly in the camp of science and modern

medicine, so I thank the giver of this advice for caring about

me so much, and letting them know that I am very comfortable

with my decision given that I really do understand this stuff.

You should of course consider all legitimate treatment

courses, but I'm firmly in the camp of science and modern

medicine, so I thank the giver of this advice for caring about

me so much, and letting them know that I am very comfortable

with my decision given that I really do understand this stuff.

That's the infusion time on the take-home pump,

so it means that once your pump is connected, you'll

show up 2 hours earlier, but 2 days later.

That's the infusion time on the take-home pump,

so it means that once your pump is connected, you'll

show up 2 hours earlier, but 2 days later.